CESARE BRIZIO

Reading Time: 15 minutes

Cesare alle prese con Pamphagus sardeus sulla Giara di Gesturi – Foto di F.M. Buzzetti

Oggi facciamo due chiacchiere con l’amico Cesare, per scoprire qualcosa sulla sua attività in campo bioacustico

Cesare, ci racconti come hai iniziato?

La prenderò molto alla lontana, perché credo che la rivelazione che c’è sotto sia interessante. Ho iniziato a fotografare a fine Anni Settanta, ai tempi dell’Università (sono laureato in Scienze Geologiche), guarda caso proprio in Sardegna, dove anni dopo avrei svolto le prime ricerche bioacustiche di un (pur modesto) valore scientifico, riscattate dalla collaborazione con l’autorevole amico Filippo Maria Buzzetti, lui sì vero scienziato e vero bioacustico. Un altro amico, Piero Fariselli, che spesso mi ha influenzato in modo decisivo, ha scatenato il processo che mi avrebbe portato a dilettarmi di Bioacustica, innescandolo in un modo assolutamente imprevisto, tanto da lui, quanto da me: alla fine del 1991, di ritorno dal viaggio di nozze in Sardegna, mi invitò a una cena a cui seguì la proiezione di diapositive. Tra le classiche diapositive di paesaggi e degli sposi, a un tratto un’immagine incomprensibile: un dettaglio a forte ingrandimento della punta di un ramoscello, mi pare di Euforbia. «E questa meraviglia cos’è?»

Piero rispose quasi imbarazzato «Scusa, scusa, questa è dell’altro raccoglitore, quello delle mie macro – non era previsto che te la mostrassi…» – e io «No, no… Mostra, mostra pure…».

Di lì a due mesi, avevo la stessa Pentax K-1000 di Piero, gli stessi flash Metz “da dentista” di Piero, lo stesso obiettivo Kiron 105mm Macro 1:1 di Piero. Per anni abbiamo fotografato assieme, azzardando anche una partecipazione ai Rolex Awards for Enterprise, con la nostra “fotografia a basso impatto ambientale” – esiste ancora qualche mia pagina Web “fossile” che ne parla –http://www.cesarebrizio.it/IMM_ARTR/Diapook.htm. Insomma: ricercavo la possibilità di dare testimonianza della biodiversità nostrana, che io per primo avevo sottovalutato, con un metodo non invasivo e con l’intento di divulgare/evangelizzare una maggiore sensibilità ambientale.

Verso la fine degli Anni Novanta il solito Piero mi dette un’altra botta decisiva, facendomi ascoltare il CD “Entomophonia” di André-Jacques Andrieu e Bernard Dumortier (https://www.discogs.com/it/Andr%C3%A9-Jacques-Andrieu-And-Bernard-Dumortier-Entomophonia-Chants-DInsectes/release/3050538), rivelandomi un’altra maniera di raccogliere e eventualmente divulgare tracce della presenza di tante specie diverse. Nel 2001, se ben ricordo, acquistai un registratore DAT portatile usatissimo ma ancora efficiente, feci rigenerare il pacco batterie, e iniziai a registrare quasi esclusivamente uccelli, soprattutto merli e usignoli, e qualche grillo e anfibio. In parallelo, facendomi prestare un PC portatile, provai a avviare registrazioni digitali direttamente su PC, sormontando la scomodità di riversamento dei nastri DAT. A orientarmi in modo decisivo verso le registrazioni del canto degli insetti fu, sai che novità!, ancora Piero Fariselli con un regalo decisivo, la splendida guida agli ortotteroidei del Veneto di Fontana, Buzzetti, Cogo e Odé, e soprattutto il CD allegato… all’epoca mai avrei pensato di arrivare a conoscere bene Paolo Fontana e Filippo Maria Buzzetti fino al punto di coautorare immeritatamente alcuni articoli scientifici con loro.

In esordio, accennavo a una “rivelazione”, eccola: la Bioacustica si presta a molti paralleli con la fotografia, può esserne il complemento, la supera da tanti punti di vista, ed in sostanza è una strategia di prospezione della biodiversità. L’animale è un’entità a molte faccette, tutte egualmente importanti, e qualsiasi descrizione esauriente della sua biologia ed ecologia deve necessariamente includere l’ambito delle emissioni sonore udibili ed inudibili che descrivono il suo perimetro esistenziale.

I miei principi guida, dai quali rarissimamente ho derogato, restano gli stessi di allora e rappresentano un livello di ingenuità un po’ controproducente, al limite dell’ipocrisia: registrare solo in natura, solo il canto di animali liberi. E non catturare mai. L’ipocrisia sta sia nel fatto che talora ho catturato (occasioni che si contano sulle dita di una sola mano, e che hanno riguardato specie interessanti o controverse), e che so benissimo che tanto la cattura, quanto la registrazione in ambiente di laboratorio, sono indispensabili.

E più di recente?

Sono andato focalizzandomi, e per certi versi diradando l’attività. L’eterno principio “un’ora in campagna, un mese alla scrivania” si applica perfettamente alle ricerche bioacustiche: come sai meglio di me, ogni registrazione è una terribile trappola che ti obbliga moralmente, in una sorta di positiva tossicodipendenza, a catalogare, postprodurre, identificare, pubblicare su Web o su carta, raccontare, discutere… Ora sono estremamente più selettivo.

Per molti anni, ho proposto le mie presentazioni sulla bioacustica, accompagnate da mie foto (talora integrate da materiale di altra provenienza, comunque doverosamente accreditata agli autori) e mie registrazioni. Queste presentazioni sono state proposte in Circoli culturali e naturalistici, Comuni, sedi di Enti Parco, Consorzi di Bonifica, gruppi di interesse di varia natura, in molte decine di edizioni. Nei primi anni, il format si chiamava “L’orecchio ingannatore”, alludendo ai complessi filtri neurali connaturati in noi: prendevo spunto dalla mia ingenua e futile ricerca del registratore «che registrasse ciò che udivo», il che ovviamente è una pretesa folle – la registrazione non è schiava della soggettività, e non esistono sistemi con lo stesso potere selettivo messo in campo dalla combinazione del nostro povero orecchio, con tutti i suoi enormi limiti, e del nostro cervello. Questo primo ciclo di presentazioni, con tanti aneddoti, raccontava in sostanza questa rivelazione: la necessità della ricerca del contatto diretto con l’animale, del silenzio, della calma. La nascita della consapevolezza che per fare una registrazione decente in natura possono occorre giorni o settimane.

A partire dal 2013, con “Audiosfera 3.0” (http://www.cesarebrizio.it/Presentazione%20Audiosfera.pdf) ho approcciato il tema in modo diverso e più generale, in termini che approssimano una visione ecoacustica, e con tanti esempi che vanno al di là dei gruppi naturali con cui ho lavorato.

Negli ultimi anni non ho fatto presentazioni e ho dedicato una parte del mio tempo alla pubblicazione di alcuni articoli scientifici, tutti accessibili qui: http://www.cesarebrizio.it/#Anchor_ScientificPapers

Da qualche anno, essendomi ritirato dal lavoro, ho molto più tempo di prima, ma esso resta conteso tra tali e tanti interessi, da rendere necessaria un’attenta pianificazione delle uscite bioacustiche. È però certo che, così come feci al tempo della mia passione per la macrofotografia (che si tradusse in un rilascio pubblico delle foto di oltre 1300 specie sulla piattaforma TOLWEB – http://www.cesarebrizio.it/IMM_ARTR/ARTHROPODA.htm – e che in parte continua nei ritagli di tempo – http://www.cesarebrizio.it/Best10/Best10.htm), di qualsiasi specie io registri, un po’ come fai tu, lascio traccia sulle mie pagine Web pubbliche sia in forma di schede (come ad esempio questa: http://www.cesarebrizio.it/BIOAC_ORTH/OrthAudioSamples.htm), sia in forma di una mappa che, da quando Google Maps non è più gratuito, è molto più brutta di prima… (http://www.cesarebrizio.it/MapAudio.htm).

Tra le soddisfazioni degli ultimi anni, grazie alla collaborazione del sempre generosissimo Prof. Gianni Pavan e di Ivano Pelicella di Dodotronic, il workshop che ho organizzato a Entomodena nel 2019, “Bioacustica, dallo stupore alla conservazione”. C’è scappata anche un’intervista su una tv locale: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XbExRM4Ilqk&feature=youtu.be .

Che attrezzature usi?

L’evoluzione è stata davvero radicale.

Quanto al supporto di registrazione, iniziai con il DAT, proseguii con il PC portatile e poi feci il salto di qualità con il registratore digitale Edirol R-09, e infine con lo Zoom H-1 che uso tuttora per le registrazioni in banda udibile. Il PC è riemerso, più di recente accompagnato da un piccolo tablet ASUS, per le registrazioni in banda inudibile.

I microfoni sono stati, negli anni, ciò che mi ha più impegnato dal punto di vista tecnico: senza mai arrivare nemmeno lontanamente al tuo livello di competenza e di autocostruzione sofisticata, dopo il primo acquisto di un microfono direzionale semiserio, un Karma DMC-942, usato anche assieme al DAT, sono partito con microfoni da PC, spesso montati su un’asticella, e accoppiati a preamplificatori autocostruiti con i kit di “Nuova Elettronica”. Più di recente, a partire dal 2012, la scoperta di Ultramic e del non udibile, con lo sviluppo del protocollo di registrazione e comparazione pubblicato per la prima volta in Brizio e Buzzetti, 2014 (http://goo.gl/Izm8w4). Ne sarebbero seguite tutte le mie pubblicazioni bioacustiche fino a quelle uscite in questo 2020.

Anche io ho dilettantescamente esplorato un aspetto che tu, Marco, hai approfondito in modo inimitabile, quello dei microfoni parabolici. Già ai tempi del DAT, avevo realizzato il primo, basato su una parabola televisiva satellitare e sul Karma DMC-942 (http://www.cesarebrizio.it/UnaParabolaPrimeFocus.pdf ). Successivamente, considerato che il tuo amico Klas Strandberg aveva pubblicato alcuni disegnetti sul sito di Telinga, rifeci il tutto con doppia capsula (riciclando quelle dell’Edirol R-09) basandomi su una plafoniera parabolica (http://www.cesarebrizio.it/UnaParabolaStileTelinga.pdf ) e su uno schema elettrico incredibilmente semplice, che giustamente ai tempi ti lasciò perplesso ma che funzionava. Poi è arrivato Ultramic 250, che mal si concilia con un riflettore parabolico. Ma, dato che ho continuato a registrare anche in banda udibile con lo Zoom H1, ho realizzato il composito basato su una delle tue parabole da 33 cm (https://www.naturesound.it/parabolic-microphone-33-cm-diameter/ ) e su uno stick di alluminio da 1 metro, montando due capsule Primo EM172 sempre in stile Telinga.

Riguardo alle registrazioni subacquee, dopo vari tentativi di autocostruzione basati su capsule microfoniche siliconate, acquistai – per poi adoperarlo pochissimo – un bell’idrofono Aquarian Audio che ho ancora e che non mi dispiacerebbe riprendere in mano in futuro.

C’è qualche specie o gruppo di specie che ti ha preso particolarmente?

Al di là dell’incontro con l’Ululone sul massiccio del Grappa, incontro di cui sarò eternamente debitore a Ivan Farronato; al di là delle registrazioni del Pelobate e del Succiacapre a Porto Caleri, e qui devo ringraziare Jacopo Richard, sono sempre stato affascinato dagli Ortotteri con canti dal forte trillo continuo. Le soddisfazioni bioacustiche della mia vita hanno riguardato soprattutto e in ordine di importanza il mitico Gryllotalpa vineae, che letteralmente corsi a registrare a Cébazan, vicino a Beziers, con un paio di giorni di preavviso per merito dei bioacustici francesi Julien Barataud e soprattutto Jean-Louis Pratz, che mi informarono tempestivamente.Era il 1 Maggio 2007: l’esperienza di quegli 80 dB a due metri dalla tana è stata indimenticabile; a ruota, e con il vantaggio accessorio di avere poi pubblicato qualcosa a riguardo, non dimenticherò mai l’incontro con il formidabile Brachytrupes megacephalus, che soggettivamente, ma senza fonometro a confermarlo, mi è sembrato capace di un canto altrettanto forte. L’ho incontrato e registrato in Sardegna nell’Aprile di due anni fa. Sempre in Sardegna (zona di Fluminimaggiore), e sempre oggetto di pubblicazione, lo splendido canto, che ben conosci, di Oecanthus dulcisonans, meno impressionante, più sottile ma non certo sommesso: l’armonioso e incessante trillo delle notti della bella stagione in quel pezzo di Sardegna.

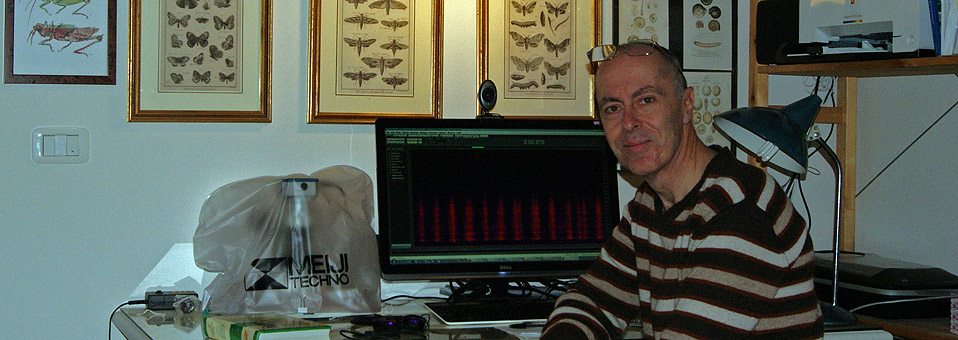

Però, se faccio un altro passo indietro e mi sposto verso gli uccelli, i primi amori restano Merli e Usignoli, animali quasi magici. La notte, vedere le staffilate colorate e le torri di armoniche dei canti dell’Usignolo materializzarsi nello spettrogramma sullo schermo del PC nel corso della registrazione resta una delle emozioni più indimenticabili della mia vita. Tuttora, attendo i primi canti di Merlo, sempre più precoci al variare del clima, e in questi ultimi anni già udibili a Febbraio, per considerare che la bella stagione sta iniziando.

Progetti futuri?

C’è già un bel po’ di materiale registrato in banda larga (con Ultramic 250) relativo a diverse specie non coperte in Brizio, Buzzetti e Pavan, 2020 (http://www.biodiversityjournal.com/pdf/11(2)_443-496.pdf ), riguardo a cui i miei autorevoli compari hanno espresso interesse a pubblicare qualcosa. Tra le specie, Pterolepis pedata e Ctenodecticus bolivari dalla Sardegna, Melanogryllus desertus dal mio giardino a Poggio Renatico. Sperando che le restrizioni legate alla pandemia lo consentano, questa primavera 2021 in Sardegna, che continuo a frequentare regolarmente, mi piacerebbe incontrare di nuovo Pamphagus sardeus. Si tratta di una specie che non ritenevo capace di emettere suoni e che comunque è pochissimo studiata da questo punto di vista: da quando, poche settimane fa, ho scoperto le registrazioni fatte da Sigfrid Ingrisch nel 1983, sogno di registrarne il canto per analizzarne le componenti ultrasoniche.

Probabilmente, meriterebbero approfondimenti anche le registrazioni di cicale fatte assieme a te in Romagna. E, a dirla tutta, mi piacerebbe riprendere con merli e Usignoli, che non ho mai dimenticato.

ENGLISH VERSION

Today we have a chat with our friend Cesare, to find out something about his activity in the bioacoustic field

Cesare, can you tell us how you started?

I will take it very far, because I think the revelation that lies beneath is interesting. I started photographing at the end of the seventies, at the time of the University (I graduated in Geological Sciences), coincidentally in Sardinia, where years later I would have carried out the first bioacoustic research of some (albeit modest) scientific value, redeemed by the collaboration with the authoritative friend Filippo Maria Buzzetti, a true scientist and a true bioacoustician. Another friend, Piero Fariselli, who often influenced me in a decisive way, triggered the process that would lead me to dabble in Bioacoustics, giving the spark in an absolutely unexpected way, both for him and for me: at the end of 1991, back from the honeymoon in Sardinia, he invited me to a dinner which was followed by a slide show. Among the classic slides of landscapes and of the newlyweds, suddenly a puzzling image: a highly magnified detail of the tip of a twig, I think of Euphorbia.

“And what is this wonder?”

Piero replied almost embarrassed “Sorry, sorry, this is from the other binder, that of my macros – I wasn’t supposed to show it to you …” – and I “No, no … Show it, show it …” .

Two months later, I had the same Pentax K-1000 as Piero, the same Metz “dentist” flashes as Piero, the same Kiron 105mm Macro 1: 1 lens as Piero. For years we have photographed together, even risking a participation in the Rolex Awards for Enterprise, with our ” low environmental impact photography” – there are still some of my “fossil” Web pages that talk about it – http://www.cesarebrizio.it/IMM_ARTR/Diapook.htm. In short: I was looking for the opportunity to bear witness to our local biodiversity, which I was the first to underestimate, with a non-invasive method and with the aim of disseminating / evangelizing a greater environmental sensitivity.

Towards the end of the Nineties Piero, as usual!, gave me another decisive blow, making me listen to the CD “Entomophonia” by André-Jacques Andrieu and Bernard Dumortier (https://www.discogs.com/it/Andr%C3%A9-Jacques-Andrieu-And-Bernard-Dumortier-Entomophonia-Chants-DInsectes/release/3050538 ), revealing another way to collect and possibly disclose traces of the presence of many different species. In 2001, if I remember correctly, I bought a very used but still efficient portable DAT recorder, I had the battery pack regenerated, and started recording almost exclusively birds, especially Blackbirds and Nightingales, and some crickets and amphibians.

At the same time, by borrowing a laptop, I tried to start digital recordings directly on the PC, overcoming the inconvenience of dubbing DAT tapes. To orient me decisively towards the recordings of the song of insects was, what a novelty!, Piero Fariselli again with a decisive gift, the splendid guide to the Orthopteroids of Veneto by Fontana, Buzzetti, Cogo and Odé, and above all the attached CD. At the time I never thought I’d get to know Paolo Fontana and Filippo Maria Buzzetti well to the point of undeservedly co-authoring some scientific papers with them.

At the beginning, I mentioned a “revelation”, here it is: Bioacoustics lends itself to many parallels with photography, it can be its complement, it surpasses it from many points of view, and in essence it is a strategy for prospecting biodiversity. The animal is a multi-faceted entity, all facets equally important, and any comprehensive description of its biology and ecology must necessarily include the range of audible and inaudible sound emissions that describe its existential perimeter.

My guiding principles, from which I have rarely departed, remain the same as they were then and represent a level of naivety that is a bit counterproductive, bordering on hypocrisy: I record only in the natural environment, only the songs of free animals. And I never capture. The hypocrisy lies both in the fact that I have sometimes captured (opportunities that can be counted on the fingers of one hand, and which have involved interesting or controversial species), and that I know very well that both capture and recording in a laboratory environment are indispensable.

And more recently?

I went by focusing, and in some ways thinning out the activity. The eternal principle “an hour in the countryside, a month at the desk” applies perfectly to bioacoustic research: as you know better than me, each recording is a terrible trap that forces you morally, in sort of a positive addiction, to catalog, postproduce, identify, publish on the Web or on paper, tell, discuss … Now I am much more selective.

For many years, I have proposed my presentations on bioacoustics, accompanied by my photos (sometimes supplemented by material from other sources, however duly credited to the authors) and my recordings. These presentations have been proposed in cultural and naturalistic circles, municipalities, offices of park bodies, reclamation consortia, interest groups of various kinds, in many dozen editions. In the early years, the format was called “The deceiving ear”, alluding to the complex neural filters inherent in us: I was inspired by my naive and futile search for the recorder that “records what I hear”, which obviously is a crazy claim – recording is not a slave to subjectivity, and there are no systems with the same selective power brought into play by the combination of our poor ear, with all its huge limitations, and our brain. This first cycle of presentations, with many anecdotes, essentially told about this revelation: the need to strive for direct contact with the animal, for silence, for calm. The emergence of the realization that making a decent recording in nature can take days or weeks.

Starting from 2013, with “Audiosfera 3.0” (http://www.cesarebrizio.it/Presentazione%20Audiosfera.pdf) I approached the topic in a different and more general way, in terms that approximate an eco-acoustic vision, and with many examples that go beyond the natural groups I have worked with.

In recent years I have not made presentations and I have dedicated part of my time to the publication of some scientific articles, all accessible here: http://www.cesarebrizio.it/#Anchor_ScientificPapers

Since a few years, having retired from work, I have much more time than before, but it remains disputed between such and so many interests, that careful planning of bioacoustic expeditions is necessary. However, it is certain that, as I did at the time of my passion for macro photography (which resulted in a public release of photos of over 1300 species on the TOLWEB platform – http://www.cesarebrizio.it/IMM_ARTR/ARTHROPODA.htm – and that in part continues in my spare time – http://www.cesarebrizio.it/Best10/Best10.htm ), of any species I register, a bit like you do, I leave traces on my public Web pages both as web pages (such as this one: http://www.cesarebrizio.it/BIOAC_ORTH/OrthAudioSamples.htm ), and in the form of a map which, since Google Maps is no longer free, is much uglier than before .. . (http://www.cesarebrizio.it/MapAudio.htm ).

Among the satisfactions of recent years, thanks to the collaboration of the always generous Prof. Gianni Pavan and of Ivano Pelicella of Dodotronic, I cite the workshop I organized at Entomodena in 2019, “Bioacustica, from amazement to conservation”. There was also an interview on a local TV: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XbExRM4Ilqk&feature=youtu.be.

What equipment do you use?

The evolution has been truly radical.

As for the recording medium, I started with the DAT, I continued with the portable PC and then I made the qualitative leap with the Edirol R-09 digital recorder, and finally with the Zoom H-1 that I still use today for recordings in audible band. The PC has resurfaced, most recently accompanied by a small ASUS tablet, for inaudible band recordings.

Microphones have been, over the years, what has engaged me the most from a technical point of view: without ever reaching even remotely your level of expertise and sophisticated self-construction, after the first purchase of a semi-serious directional microphone, a Karma DMC-942, also used together with the DAT, I started with PC microphones, often mounted on a stick, and coupled to self-built preamplifiers from “Nuova Elettronica” kits. More recently, starting from 2012, the discovery of Ultramic and of the inaudible range, with the development of the recording and comparison protocol published for the first time in Brizio and Buzzetti, 2014 (http://goo.gl/Izm8w4). All my bioacoustic publications would follow, up to those released in this 2020.

I too have amateurishly delved into an aspect that you, Marco, have explored in an inimitable way, that of parabolic microphones. Already at the time of the DAT, I had made the first one, based on a satellite television dish and on the Karma DMC-942 (http://www.cesarebrizio.it/UnaParabolaPrimeFocus.pdf). Subsequently, considering that your friend Klas Strandberg had published some drawings on the Telinga website, I did everything again with a double capsule (recycling those of the Edirol R-09) based on a parabolic ceiling light (http://www.cesarebrizio.it/UnaParabolaStileTelinga.pdf ) and on an incredibly simple wiring diagram, which rightly left you perplexed at the time but that worked. Then came the Ultramic 250, which does not fit well with a parabolic reflector. But, since I continued to record also in audible band with the Zoom H1, I made a composite based on one of your 33 cm dishes (https://www.naturesound.it/parabolic-microphone-33-cm-diameter/) and on a 1 meter aluminum stick, mounting two Primo EM172 capsules, again in Telinga style.

With regard to underwater recordings, after several self-construction attempts based on silicone microphone capsules, I bought – and then used it very little – a beautiful Aquarian Audio hydrophone that I still have and that I wouldn’t mind taking back in the future.

Is there any species or group of species that has particularly gripped you?

Beyond the encounter with the Yellow-bellied toad on the Grappa massif, an encounter to which I will be eternally indebted to Ivan Farronato; Beyond the recordings of Pelobates and Nightjar in Porto Caleri, and here I have to thank Jacopo Richard, I have always been fascinated by the Orthoptera singing with a strong, continuous trill. The bioacoustic satisfactions of my life concerned above all and in order of importance the legendary Gryllotalpa vineae, which I literally ran to record in Cébazan, near Beziers, with a couple of days’ notice thanks to the French bioacousticians Julien Barataud and above all Jean-Louis Pratz, who informed me promptly. It was May 1st 2007: the experience of those 80 dB at two meters from the den was unforgettable; next, and with the additional advantage of having later published something about it, I will never forget the encounter with the formidable Brachytrupes megacephalus, who subjectively, but without sound level meter to confirm it, seemed capable of an equally strong song. I met and recorded him in Sardinia in April two years ago. Still in Sardinia (Fluminimaggiore area), and again the subject of a publication, the splendid song, which you know well, of Oecanthus dulcisonans, less impressive, more subtle but certainly not subdued: the harmonious and incessant trill of the nights of summer in that piece of Sardinia.

However, if I take another step back and move towards the birds, the first loves remain Blackbirds and Nightingales, almost magical animals. At night, seeing the colorful lashes and harmonic towers of the Nightingale songs materialize in the spectrogram on the PC screen during the recording remains one of the most unforgettable emotions of my life. Still, I await the first songs of Blackbirds, more and more precocious as the climate changes, and in recent years already audible in February, to consider that the good weather is beginning.

Future projects?

There is already quite a bit of material recorded in broadband (with Ultramic 250) relating to different species not covered in Brizio, Buzzetti and Pavan, 2020 (http://www.biodiversityjournal.com/pdf/11(2)_443-496.pdf ), about which my authoritative partners have expressed interest in publishing something. Among the species, Pterolepis pedata and Ctenodecticus bolivari from Sardinia, Melanogryllus desertus from my garden in Poggio Renatico. Hoping that the restrictions related to the pandemic will allow it, this spring 2021 in Sardinia, which I continue to frequent regularly, I would like to meet Pamphagus sardeus again. It is a species that I did not think capable of emitting sounds and which in any case is very little studied from this point of view: since, a few weeks ago, I discovered the recordings made by Sigfrid Ingrisch in 1983, I dream of recording its song to analyze its ultrasonic components.

Probably, the recordings of cicadas made with you in Romagna deserve further study. And, to be honest, I’d like to get back to blackbirds and Nightingales, which I have never forgotten.

Commenti recenti